Trending Now

- IPL 2024 begins with a bang. First contest between CSK and RCB.

- Election commission allots mike symbol to Naam Thamizhar Katchi

- AIADMK promises to urge for AIIMS in Coimbatore, in its election manifesto.

- Ponmudi becomes higher education minister.

Tamilnadu News

Poison In Your Food: Part 2

![]() February 29, 2020

February 29, 2020

Is organic farming the one shot solution to curb high pesticide usage?

With a slew of measures ambitiously finding place in the annual budget of India and talks of an organic promotion policy under preparation in Tamil Nadu, The Lede investigates the state of agriculture in Tamil Nadu and finds out whether organic is really the solution it is touted to be. 60 year old RP Krishnan is a happy man. Having been a farmer for more than 40 years, it was only three years back that he says he hit the magic formula – organic farming.

“Earlier I used to grow crops in my own land near Oddanchatram for almost 30 years,” he says. “I grew vegetables like everyone else. For almost 20 years I used traditional methods and later like everyone else, I too took to using chemicals. But I wasn’t making any money. I was spending everything in buying pesticides and chemicals,” says Krishnan. 11 years back, water shortage forced Krishnan to take a 6-acre patch of land which had sufficient water near Sriramapuram on lease and shift from his home.

“For the first 8 years here, I grew sugarcane,” he says. “Sugarcane always makes you feel like you are having a lot of money. But the day the money comes, all the people I borrowed money from will also come and I would be left with nothing but a bit more debt. It was an exercise in futility.”

RP Krishnan, an organic farmerPhoto credit: Jeff Joseph

“Three years back, one of the neighbours, Ajay, recommended me to try organic farming,” says Krishnan about how he took to organic farming. “Since I hadn’t been saving anything inspite of farming for all these years, I thought about trying it out and planted onion in 1 acre of the land. While a neighbour who had used fertilisers and chemicals in half an acre got a yield of 4 tonne, I got a yield of 5 tonnes of native onion from one acre. He was spraying chemicals every 8 days apart from the fertilisers used.

When we sold it, our onion sold for Rs 40 and he got a net profit of Rs 50,000 after covering an expense of Rs 1,00,000 while I got Rs 2,00,000. My only expense was the Rs 50,000 needed for labour. His onions had root rot issues inspite of using all the chemicals.”

The success encouraged Krishnan to go organic on the entire stretch of land.

Now Krishnan has planted onion which he says will be ready in two months’ time. His last crop, brinjal, earned him a good enough profit for him to be able to make a deposit in the bank which he says he can draw from to meet the labour and other expenses of future crops.

“As long as one is lazy and trusts the shopkeepers, you will continue to make losses,” says Krishnan seated in the shed on the side of his small house calling on more farmers like him to take to organic farming.

“Some people just sit in their homes and call the shopkeepers or send others to buy the chemicals for their crops. It is this which leads to their destruction. The shopkeepers will cleverly say there is one chemical for the big pest and one for the small one or something like that and make you buy more than necessary. This is how they work.

They will even come to your farm wearing white clothes, riding bullets (motorbikes) and tell you what to buy and spray. What every farmer should understand is that shop owners work for their own profit. I am speaking from my own experience. Whatever extra money one may get by using chemicals will be spent on buying the chemicals itself. There is no point.”

Krishnan has his reasons. Before his organic crops turned out well, Krishnan had been buying inputs by borrowing money.

“I used to owe money to two money lenders at a time,” he says.

One of the reasons why Krishnan finds organic farming lucrative is that Krishnan himself makes the necessary organic inputs thereby also removing his dependability on external inputs and thus the cost of production.

“I myself make the panchakavyam and fish acid for my farm,” he says. “Now I am relieved that I don’t have to borrow just to plant a crop. I want every farmer to turn to organic farming. One can grow crops without giving any money to the chemical shops.”

But organic inputs are not limited to the few that can be prepared by the farmers themselves. Just like in inorganic farming, organic farming too has begun to come with their own share of specialised treatments needing spending out of the pocket, all thanks to the newfound interest of private entities who come charming farmers with nano technology or other fancy marketing catchwords.

Krishnan’s son Mahendran, a fulltime farmer who is also preparing for government exams as he finds it difficult to get good marriage proposals being a farmer, says the high cost inputs are a trap.

“As long as one buys all the fancy branded inputs for your crops, organic farming is going to be extremely difficult to be sustainable. With the high costs of production, the farmer will have to get very high rates to make a profit. It won’t be much different than what is happening with inorganic input driven farming of today. The only difference will be that they won’t have the issues of pesticides and chemicals in vegetables. But a farmer will never have the means to ensure it is so.

That is why in my opinion, whoever is doing organic farming should stick to preparing everything oneself and not get into the trap of buying inputs. If you are willing to put in a bit of work, one can easily implement zero budget farming. But if you ask me, high input driven farming is where things are going. It is impossible to control the corporates getting into the field. It is for the farmers to be educated and believe that high input spending is not necessary to make profit. Somewhere one has to think in terms of returns too.

All first time organic farmers fall for the trap of input dependent farming. Later they may learn. They should. One can never trust the shopkeepers,” he warns.

High Input Organic Farming

Nagaraj, who owns 30 acres of land in total has been into organic farming for three years and practices a high input strategy to farming.

Organic farmer NagarajPhoto credit: Jeff Joseph

“See, organic inputs are costlier than inorganic inputs,” he says. Nagaraj buys high cost inputs sometimes directly from the company itself, thereby saving the commission pocketed by shops like that of Raj Kumar.

He lays out the various inputs he uses in his farm and makes his point clear.

“See I have planted Papaya Red Lady variety. I am growing them by using 100% organic methods. What I feed them continuously are waste decomposers, fish acid and EM which I myself prepare.”

This is much the same as used by Krishnan. But pest control and other treatments is where Nagaraj spends more on.

“For sucking pests spraying of a bio-wrap spray is used. It costs Rs 1000 per bottle. I just used 4 bottles for the Papaya. All of them are costly. Organic fertilisers cost Rs 300 per kg. They have to be given once in 30 days. We have to use 2 kg per acreage for long duration crops whereas for short duration crops, the dosage is 6 kg per acre and has to be given monthly once.”

This alone comes to Rs 600 per month for long duration crops and Rs 1800 for short duration crops.

“This you spray over 5 acres, costs Rs 1000,” he shows another bottle. “Sucking pest controller costs Rs 950 per 2 acre. This costs Rs 1000,” he shows one bottle after the other. Plant protectors, stress metabolite, bio-wrap, the list goes on.

“I have to use these organic inputs so as not to cause problems for the buyer. If after they buy and some chemical or other contaminants are found in the produce, my buyer will lose credibility in the market and so will I,” he says. “So I have to be extra careful. But eventually they even out as while inorganic inputs have to be applied thrice a month, in organic, we can make do with just twice. And also, when selling, organic products get a higher price than inorganic which makes it profitable.

Last time I got a price of Rs 40 per kg when the market rate of inorganic was Rs 35 per kg. So it does even out. But this is possible only for big farmers. Small farmers find it difficult to get a better price for organic produce. They often just get whatever it is that the market pays for inorganic produce.

When you look at big farmers, one can find bulk takers because of the sheer scale and owing to the demand for organic produce in the market.”

Small farmers he says cannot be expected to do this.

“It is only after a pest attacks that small farmers start searching for solutions. And since they don’t spend time on research early on, it is difficult for them to get solutions. They will search around in shops and go with whatever they say or give which may or may not be effective or even organic. As things stand now, it is difficult for small farmers to successfully do organic farming,” he says.

But farmers like Mahendran and Krishnan insist they are all the better for not using costly inputs and recommend small farmers to do the same instead of trying to emulate input dependent farming which big farmers resort to.

“There are solutions for all kind of problems in organic farming,” says Mahendran. “It may be a little labour intensive though.”

The labour needs as well as the centrality of owning cattle in order to be able to make most organic inputs leads many to go looking for over the counter solutions. This in turn leads to a dependence on shops and input heavy farming.

The Lede spoke to Raj Kumar, a small shop owner dealing with organic inputs in Kannivadi area of Oddanchatram to find out how things stand.

A Bias Towards The Brands

“I started off by preparing vermin compost,” says 34 year old Raj Kumar.

Raj Kumar who earlier worked in Tirupur as a supervisor in a T shirt factory shifted back to his village two years back when faced with widespread closures there.Later, he underwent training in organic farming in MSSRF and himself shifted to organic farming on the one and half acre land he owns.

“The yield is less but I am continuing with organic,” he says.

The shop he runs is a one room enclosure wherein he sells branded organic products alongside the various self-prepared organic components like Panchakavyam, EM 2, and fish acid. While some are prepared by Raj Kumar, others are brought for sale by farmers like him who look at it as a source of income.

Raj Kumar sells organic inputs, both branded and unbrandedPhoto credit: Jeff Joseph

“It is difficult to get smaller farmers to trust the methods,” says Raj Kumar about the results of his own efforts to popularise organic farming so as to build customers for his shop.

“Bigger farmers look at the larger picture and they have better capabilities to arrange for the inputs,” he says. “If shops such as mine open everywhere, there are chances more people would shift to organic farming. Right now the smaller farmers accidently come here asking for chemicals and when said we don’t sell them, they just walk away without even caring to find out what it is that we sell.

At the same time, bigger farmers travel long distances just to buy inputs. But there is a small and growing community of farmers coming to organic,” he insists.

“But small landholders are sceptical still. They are in the clutches of the chemical shops. The biggest advantage with organic produce is that there is no poison anywhere. Everything is natural. Everyone knows they are eating poison but still many aren’t changing,” he says complaining about the general preference of farmers to grow chemically aided produce.

“If you ask me, I think people will shift to organic farming in 5 to 10 years. I printed and distributed a thousand notices trying to inform farmers in the area about organic farming. Only 5 turned up,” he says.

“One of the reasons why farmers are sticking with inorganic inputs is that the shops give inputs on advance even up to the tune of Rs 50,000. This encourages farmers to buy and use more and more. The inorganic inputs have a high margin. It is as high as 70% for pesticides and the like. This is why there are so many shops selling chemicals. Here in Kannivadi itself there are four shops selling chemical inputs. Packaging is another factor,” he says.

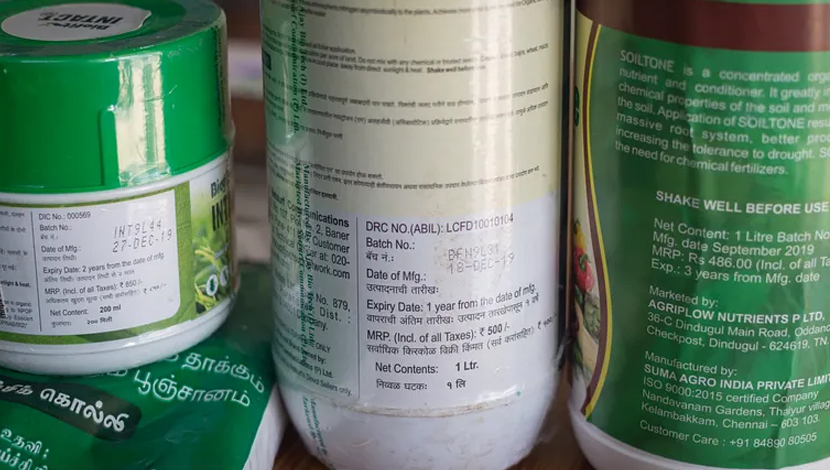

“The chemical packaging with their plastic coated bottles and branding have gained acceptance and widespread credibility. This is seen even amongst those buying organic inputs,” says Raj Kumar.

High cost branded organic inputsPhoto credit: Jeff Joseph

“We find it difficult to sell the Panchakavyam that the farmers here bring and put up for sale.”

While the farmer prepared ones, sold in 1 litre bottles, sell for Rs 100, the branded one costs double and more.

“In general, people trust higher priced stuff,” he says.

Pricing of many organic inputs suggest there is not much difference between the methods used by organic and inorganic products.

Organic inputs with MRP of Rs 1000 is sold for Rs 750 and below after discounts which would seem ridiculous. But this is seen across almost all branded organic inputs.

Inspite of this Raj Kumar says, there is enough margin when selling branded products.

Why Organic Farmers Are Lured To High Input Farming

Dr Rengalakshmi, Director of Ecotechnology program of the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation explains why even organic farmers are gravitating towards input dealers.

“Some of the extracts used in organic farming is labour intensive. It is not as much about the number of labourers needed, as much as the care and number of times they need attention. Farmers have other engagements and naturally they find it difficult to give enough care.

Sometimes, well doing farmers who make a name for themselves, move up from farming and start selling their own products. Many small farmers with no means to prepare everything themselves become dependent on them.

There has also been entry of a lot of companies selling inputs such as bio-fertilisers and plant protectors. The advertisements they run also influences farmer decisions. With all of these the input costs have been going up. But if done properly, organic inputs should cost only one-third of that of inorganic.

One other reason pushing farmers towards higher priced and branded inputs is that for organic inputs the inputs have to be protected from the sun and maintained with care. Sometimes the inputs produced by farmers themselves are contaminated and won’t have the desired effect,” she explains.

This trust deficit is exploited by private players.

“Such experiences make farmers stick to products seen as reliable or promising.”

According to shop owners like Raj Kumar, the most expensive is seen as the most reliable and credible option by farmers when buying.

“The issue is that too many private people have started producing bio-fertilisers, bio-immaculates and bio-pesticides,” says Dr E Somasundaram, HoD, Department of Sustainable Organic Agriculture, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University.

“This is happening at the same time when agricultural universities are creating and supplying cheap alternatives for the farmers. Government has put in place its own infrastructure and depots for delivery of the products. But as the private players are much more proactive, they provide door delivery even in the interior places. Thus farmers end up paying large sums while government inputs lie wasted in godown.

Ideally, all inputs should be prepared in the farms itself. In general, if the procedures are followed, the farmers themselves will be able to produce whatever is needed without much variation in quality. The cost of production of organic is supposed to be far cheaper as everything can be self-prepared. Dependence on inputs will change the scenario.

The costs of inputs sold through shops is high as their overhead costs are high. They have to recover transportation costs, marketing and advertisement charges, commissions to shop owners and what not. As things stand now, it is difficult for all farmers producing organic produce to get a higher price good enough to compensate for a high input cost farming. Also if the produce is made unaffordable for the common people, what is the purpose of growing them,” asks Somasundram about the trend to overcharge organic products.

“When it comes to fetching good price in the market, volume is the king,” he says. “Whoever can provide high volumes can have a say in the price. Small farmers selling 20-25 kgs at a time wouldn’t have any bargaining power. So it is all the more important for them to stick to low input dependent organic farming. As of now the number of certified organic farmers in Tamil Nadu is only 4500,” he says.

“This is after including the many clusters and farmer group members. So if you see in the overall picture the numbers are minuscule. The total area under cultivation by these farmers is just 31,000 acre (13000 hectare). That is why the government has also been slow to come out with a policy,” he says. “A policy note had been prepared.”

But Dr Rengalakshmi of MSSRF says the number does not actually capture the full picture. “Many small farmers have adopted organic farming without applying for organic certifications. The numbers could be far higher if they are included.”

RP Krishnan who has been into organic farming is one of them. Though the costs of organic certification is low, they cannot apply for certification as they do not own the land they have been cultivating, they say.

But the growing popularity of organic products and the interest that many private entities have been showing in organic farming suggests that there is money to be made soon enough.

The more one looks closely, the more it seems that the organic farming is emulating their inorganic counterparts. Though still in its infancy, it seems it will not be long before organic farming too falls prey to the same input industry trap waiting in the wings.

Before leaving his shop, Raj Kumar shows a small packet of branded bitter gourd seeds in a packet having a few of them and says, “This costs Rs 20.”

He pulls out another packet of farmer sold seeds and stacks them side by side. The farmer variety has many more seeds and also costs Rs 20.

“Who will buy them?” he asks.

“Even if they don’t have the money, farmers borrow and buy the costlier one.”

It could be a sign of the times to come for organic farming as well.