Trending Now

- 830 voters names go missing in Kavundampalayam constituency

- If BJP comes to power we shall consider bringing back electoral bonds: Nirmala Sitaraman

- Monitoring at check posts between Kerala and TN intensified as bird flu gets virulent in Kerala

Columns

What’s wrong with ‘Make In India’ and how it can be fixed

![]() February 21, 2016

February 21, 2016

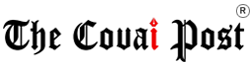

Satyen K. Bordoloi

The Make in India week gets underway in Mumbai from tomorrow. A flagship initiative of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it is not just the business world that has high expectations from it, but also the Indian middle class.

However, if the event and the basic idea intend to truly do good for the nation, it has to go beyond rhetoric and face ground realities. That is what Prof. Jairus Banaji, Research Professor, School of Oriental and African Studies, London and a published author, believes.

On February 5, 2016 he gave a lecture on ‘A short history of the employees’ unions in Bombay, 1947-1991,’ under the aegis of Centre for Labour Studies at the Durbar Hall of the Asiatic Society, Town Hall, Mumbai. Prof. Banaji dispelled many myths about labour unions in the country and talked about how they raised the level of life in the nation and its people.

While his prepared talk tackled the pre-liberalisation years i.e. pre-1991, in an impromptu speech after the talk, he highlighted what has happened since and how its repercussions can be seen in the Make In India campaign and what it can do to truly live up to its potential. Below are excerpts from that impromptu speech.

“There has been a wholesale de-unionization of the labour market since 1991 and we have seen the expansion of the contract labour sector massively. You have seen a drastic shrinkage of permanent employees. Once companies used to claim that they offered job security. By the 80s and 90s ‘job security’ had become an abused term in the management discourse. So there is a complete shift in industrial relations culture from the 70s into the 90s.

The problems that trade unionism faces today have to be discussed in a different light because it’s no longer possible simply to relaunch the employees movement of the 1950s and 60s. That whole cycle is over. However, building on the lessons learnt in the past we can go forward with a much bigger vision of how unions can make a difference in the lives of millions of workers and wage earners throughout the country. Because the bulk of the labour force isn’t unionised today. Something like 87% of the labour force is out of unions.

One important factor in all of this is the state. It is the elephant in the room. Behind the conflict between labour and capital, lies the shadow of the state. The state can make a huge difference depending on which way it turns the balance. In the 1950s and 60s we had a government that was not overtly opposed to labour and trade unions leading to a different public policy and outlook. By the 1970s and 80s, government attitudes had hardened.

It was governments which encouraged management to subcontract. The initiative was taken by the state not by capital. Subcontracting mushroomed after the 1980s largely because the state pushed capital into doing so. On what grounds? On ideological grounds because it was believed that it will be good to disperse employment, manufacturing and investments so that all parts of the country can have access to employment and industry. That was the ostensible rationale and of course from the point of view of companies it would cut costs dramatically.

However if you look at this as an industrial policy, it fragmented capacity. That meant that capital could generate economies of scale. They just could not become competitive internationally. Thus, as soon as international competition became a serious issue in the 1990s, Indian capital was not in the picture. A lot of these plants had to close down because they were globally uncompetitive.

So I think that the root cause of the problem lies in this idea that you do not allow companies to expand capacities on an existing plant on the argument that it is good to disperse employment throughout the country, give all parts of the country a chance to have industry and industrial employment. So you freeze capacity in a major metropolitan market like Mumbai, and ultimately you render those establishments uncompetitive because they cannot generate economies of scale to remain competitive.

You have all heard a lot in the last one year about Make in India. Clearly the vision is that to make India into a global manufacturing hub. But on what basis? That is not spelt out so clearly because it is politically embarrassing for them. But the other day Gadkari referred to it indirectly. He used the word labour intensive. Now what’s going on here? You are making India a manufacturing hub in terms of what, labour intensive industries? Large concentration of low wage labour is supposed to make India a manufacturing hub?

It is a program that will not work. Why? Because on your doorstep lies Bangladesh. Beyond that lies South-East Asia. Look at Japanese industry, Japanese capital, they have done it. It’s called race to the bottom. India will not win the race to the bottom. Large international firms came to this country because labour was educated, it was qualified, it was literate even in English, and it was flexible. Capital was attracted to the Indian market not just because of the size of the domestic market but because labour has certain assets and qualities which international firms found attractive.

Narendra Modi is selling India in terms of a vision of labour which is an antithesis of that. He is not spelling it out openly but basically he is saying it is unorganised labour, it is labour which has no union rights, it is contract labour, it is labour willing to live at close to subsistence level wages, it is labour without reproduction costs which was subsidized by the state.

It is labour which is basically thrown to the full blast of the market. He is not willing to spell out those elements because that is not good for propaganda value. But essentially that is the message which has been communicated to international companies that: come to India, invest in India, you’ve got a vast reservoir of cheap flexible labour which you can dominate. It is not going to work because at that level India will not win the battle of competition.

Therefore the first thing we need is a serious industrial policy. We just do not have an industrial policy today. This is a government which is more interested in saying how much the value of the deal is, announcing it to the papers next day a 4 and a half billion dollar value defence contract, bullet trains that will cost 90,000 crore etc.

The flaw in the argument is that this is all supply driven. It is not being driven by our demands, our social needs, by what our economy needs, what our society needs. It’s all supply driven. The Japanese are willing to offer the bullet train, California is willing to offer digital platforms, France is willing to offer defence deals, Russia is willing to offer defence deals and nuclear reactors, UK is willing to finance infrastructure… all of this is supply driven. Not one of these programs is a function of a coherent public industrial policy.

Secondly if you think you are going to make India into a manufacturing hub by exploiting cheap labour, then you are basically not addressing the fundamental issue of capital in this country which is that the domestic market will not expand.

When unions were strong, wages were pushed up, when wages went up domestic demand expanded, that was the beginning of the white goods industry in a region like Maharashtra. The white goods industry expanded largely fuelled by demand from working class families. It is a classic example of how strong unions, feed into an expanding market, which in turn feeds into an accumulation process. This is the model you need to generalise throughout the country.

Therefore, no Make in India without strong unions, without collective bargaining. That should be the first condition. Strong unions are not a hindrance to large scale industries but are a fundamental part of it; unless that is you seriously think that the working class is simply a mass of slaves. That vision is not compatible with democracy, with the modern world. The working class is a class which is part of the rationality of the large scale industry.

It is created by that rationality. This is the class that embodies within itself, all the skills, the idea, the intelligence which knows how to run a production process, often much better than managers. Of course that is a separate issue of whether managers are also workers. A lot of technical managers are workers. The entire collection of these workers, whether they are blue collar or technical or white collar is what Marx called the collective worker.

The collective worker is a repository of industrial intelligence, of skills, of the rationality of large scale industry. You cannot build a competitive industrial sector, by destroying the working class, by offering it to international capital, or international business as cheap slave labour.

That will not work. That is why Modi’s Make in India, apart from being un-thought out, apart from being a sleight of hand will not succeed as an industrial policy. Strong unions, strong collective bargaining rights are the key. And what does strong union mean but that those union rights have to extend to the bulk of the labour force in the country.

Imagine the 87% which is not organised today, if it were organised into unions, what would you call that? If the 87% were organised today, it would be nothing short of a revolution.”

Disclaimer:The views expressed above are the author’s own