Trending Now

- 830 voters names go missing in Kavundampalayam constituency

- If BJP comes to power we shall consider bringing back electoral bonds: Nirmala Sitaraman

- Monitoring at check posts between Kerala and TN intensified as bird flu gets virulent in Kerala

Tamilnadu News

Why Are Elephants Dying In Tamil Nadu?

![]() July 4, 2020

July 4, 2020

On the evening of June 28, a male elephant, estimated to be aged 12, was first sighted appearing sickly and starved near Pudukkattu, coming under Sarak forest area, near Bethikkuttu of Coimbatore.

This was not the first elephant to be spotted in the area in this condition.

By evening the following day, the sickly elephant had reached Karupparayan temple near Bethikkuttu where it collapsed.

The adolescent elephant was intermittently checked upon by four wild tuskers who would nudge it to get it to stand by itself as the medical team stood by. With no power in its front legs and its body starved thin to the bones, the young one could not move.

The Assistant Forest Officer of Kota Kovil, the Forest Animal Officer and the Forest Veterinary Officer, Coimbatore extended it medical treatment on June 30. With no significant improvement in its health inspite of three continuous days of treatment, by the evening of July 02, the veterinary officer assessed that it had only 24 hours of life left.

By the afternoon of July 03, the elephant became motionless.

But its death could be verified only at 3 pm once the other tuskers moved away.

The doctor upon examination declared the elephant dead. It is believed to have died by 11:45 am.

While the post mortem report is yet to be received, a similar elephant death discovered a day before, within three kilometres of the area raises questions.

What are these elephants dying of?

The Other Deaths

A total of 12 elephants have died in the Coimbatore division so far this year.

The division consists of seven ranges.

Of these, eight elephants have died in Sirumugai range alone. The Sirumugai range is part of the larger Coimbatore division.

On July 02, two elephants were found dead under the same forest range.

One of these was a female elephant, around 40 years old which died in Kandiyur of gunshot wounds.

A crop raider, she is said to have been allegedly killed by farmers who have since been arrested.

But the other was a body of another young male found in Lingapuram, which is around three kilometres from Karupparayan temple where the latest elephant death happened.

The body appeared bloated and had carried no signs of wounds.

The elephant, a young male, aged around 14 years died of an undetectable illness as per officials who refused to give the post mortem report. More elephants have died in a similar fashion.

On June 23, another elephant was found dead under similar circumstances. It too was a young male with an estimated age of 14 years.

This brings the total elephant deaths within the first six months of 2020 in the Sirumugai Range of Coimbatore division to eight.

This includes the three elephants which have died within a span of 10 days and the one which died of gunshot wounds.

While no explanation has been forthcoming as to the cause of death, it is seen that these elephants have starved to death.

But instead of testing samples to find out the truth, the Tamil Nadu Forest Department appears to be more interested in shifting blame.

Explanations By Forest Officers

The explanation given by the officials on the ground is that the young elephants were starving to death as they had little to eat in that particular stretch of forests in Sirumugai range.

The surroundings of Sirumugai forest range is covered with Eucalyptus and Acacia plantations, they say.

With edible vegetation lost, they say that the elephants have been eating these unpalatable plants, getting sick and drinking water to try and get the toxins out of the system.

Asked why the elephants would not move out to greener areas, they say that given that the large water body nearby still had sufficient water, the elephants would not move.

Activists rubbish these claims.

“Elephants will never eat eucalyptus,” says Macmohan a wildlife activist.

“The areas falling under the Sirumugai range are greener than most other places,” says another activist. “Moreover, for an elephant, water bodies are not a big deal. Can’t they swim over to the other side?”.

But NVK Ashraf, Senior Director of the Wildlife Trust of India, while not dismissing possibility of a disease outbreak, told The Lede that the forest department’s explanations need to be looked into.

“What we are seeing in Coimbatore is most likely the case of a trapped population,” said Ashraf. “Elephants are used to following their traditional migratory patterns. So even if there is food in another area, they will still migrate out as is habitual.

But when they don’t get any food in the paths they follow, they starve and die. I understand that all the deaths are happening in the same area where such deaths was not seen until recently.

Faulty landscape practices such as trenches and wire fencing which though they may be legal, have adverse effects on elephant movement. As a result of these, landscapes are affected and human induced disruptions are the cause.

By excluding an area by fencing off the elephants, while there may not be anything illegal, the elephants are being denied access to their traditional routes. As a result, these things are bound to happen.

For instance, in Sri Lanka, in one place where they had fenced off a traditional route, in spite of there being other passable areas, an entire herd just stood next to the fencing and eventually 20 odd elephants died of starvation.

You cannot close such cases by sending a veterinarian and doing a post mortem alone. It could very well be that it is not due to disease either,” he stated.

“Nothing Abnormal About Deaths”

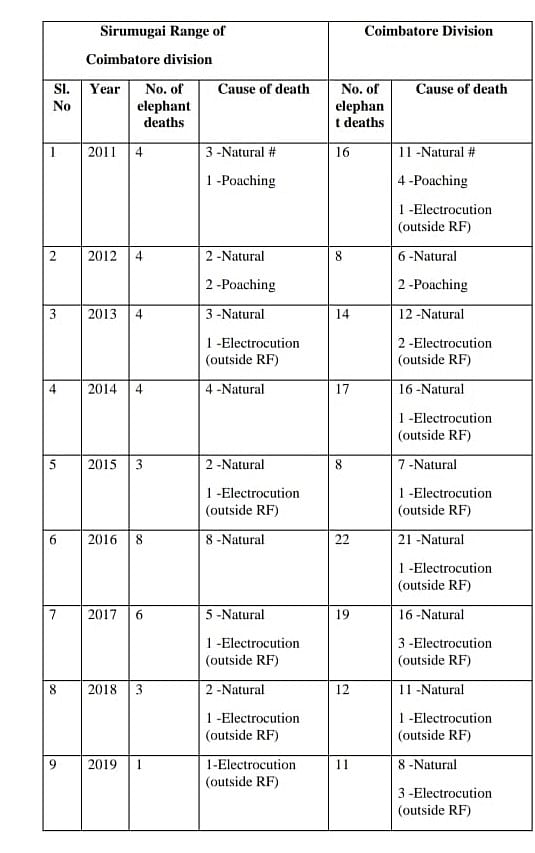

A forest official in the know refers to statistics to suggest there was nothing abnormal in the number of deaths this year.

“Year wise data is as follows,” said the official on the condition that his name not be revealed, arguing that there was nothing unusual this year as compared to previous years in the entire Coimbatore Forest division.

Source: TN Forest Department

“So deaths are common. It is not abnormal this year as alleged. Kindly don’t get carried away by tales created with ulterior motives,” said the officer.

“I have collected data about elephant deaths in Coimbatore Division in last ten years. Totally 139 elephants died out of which 117 are from natural causes. On average 14 elephants die per year. Deaths due to natural causes are not in our hands. For unnatural deaths like electrocution and poaching, the culprits are booked.

It is alleged that disease is an excuse. It is a baseless allegation without any evidence. Under the Wildlife Protection Act even a member of the public can prosecute the case if he is having evidence to prove the offence. The death in Sirumugai is almost one-third of total deaths for which I have already given the reasons.”

But the table above shows that compared to the few deaths in the Sirumugai range in the past two years, the first six months of 2020 alone have registered a total of 8 deaths. This is a sharp increase.

In spite of this Tamil Nadu’s Forest Department officials seem least inclined to conduct in depth tests to ascertain the actual cause of death. All of these elephant deaths have been categorised instead as “natural deaths”.

While the forest officials say that samples are being sent for further tests, activists are not hopeful.

“There are no tests results, only tests. You ask about the results from a year back or last weeks’, they will have nothing still,” says Macmohan.

“Without test results we cannot ascertain cause of death. Without cause of death we have nothing. But that is how the forest department works,” he says.

Officials privately admit that they will need to get permissions from those higher up in the hierarchy to see if these deaths are part of an outbreak.

An official also said there are plans to put up a team to look into any outbreak.

But this statement came from officials only after The Lede posed a question to them as to whether they were aware of the mass elephant deaths in Botswana.

They were unaware and that is perhaps more worrisome than anything else.

What Will State & Centre Do?

How does the state and the centre plan to prevent such elephant deaths from occurring?

A scheme that was initiated in 2011 and continued up to 2016 may provide an answer to the shortage of food theory.

In December 2011, the state government passed a Government Order directing Green Fodder Banks to be cultivated as a pilot project across 240 hectares of forest. Of this, 100 hectares was to be cultivated in the forests in Walayar, Karamadai, Mettupalayam, Boluvampatti, Periyanaickenpalayam and Sirumugai.

Borewells were dug in areas where elephants traditionally migrate within forests and solar powered motors were fitted for irrigation.

In each area, around 15 hectares of forest land was demarcated for cultivation of wild mango, wild jackfruit, bamboo and grass varieties preferred by elephants. The idea was to keep wild elephants inside the forest with food availability rather than forcing them to stray into human habitations.

The Tamil Nadu government sanctioned Rs 20.87 crore for this scheme for a period of five years from 2011-12 to 2015-16.

“The scheme worked well in some areas but in others, it did not do so well,” said a forest department officer who did not wish to be named. “For instance, in Boluvampatti, the bamboo forest has grown very well. In other areas, the elephants ate up the crops when they were young itself,” he said.

An adult elephant needs between 240 to 260 kg of food every day.

“What we provide will not be enough for the wild elephants,” said an officer of the forest department about the Green Fodder Bank scheme. “We can only do what is possible within our limits.”

What will the state and the centre do next? Will they conduct necessary tests, make results public and take necessary action to save elephants from dying rapidly?

“An expert committee has to be formed comprising of multidisciplinary experts from within and outside Tamil Nadu and asked to study and submit a report investigating the reasons as to why these deaths have happened in a very localisd area,” said NVK Ashraf of the Wildlife Trust of India.

This is only the first step. And this needs to be completed rapidly if the state expects to prevent further elephant deaths.